Executive Summary

The Africa Climate Summit in September 2025 marked an important political moment as leaders launched the Africa Climate Innovation Compact and the African Climate Facility to mobilise substantial annual resources. These initiatives reflect a clear determination to assert African ownership of the climate finance agenda. While finance flows to Africa have grown, they remain well below estimated needs, with a continuing imbalance between mitigation and adaptation despite the continent’s acute vulnerability. The declining share of concessional resources, coupled with rising debt service obligations, raises concerns that climate finance is reinforcing rather than easing fiscal stress. Access to funds is also uneven, concentrated in a handful of countries with stronger institutional frameworks, leaving fragile and smaller economies on the margins. Private sector engagement remains limited, particularly for adaptation projects that lack predictable returns. Together, these dynamics illustrate a widening disconnect between the resources mobilised and the continent’s sustainable development priorities, positioning climate finance as both an opportunity for transformation and a critical source of ongoing vulnerability.

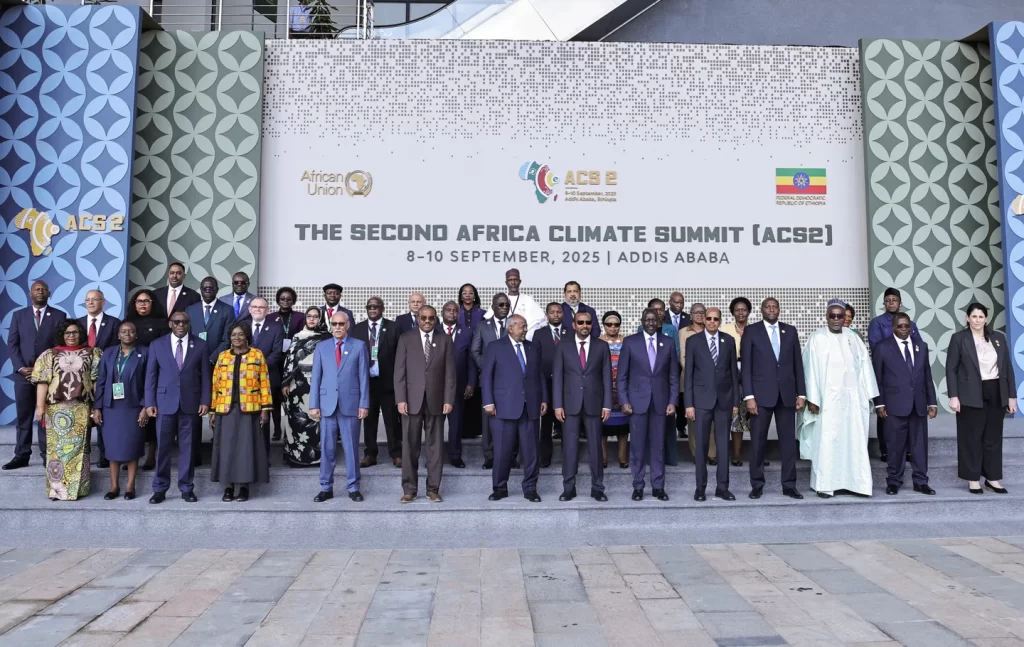

The Africa Climate Summit held in Addis Ababa in September 2025 brought renewed attention to the continent’s climate finance agenda. At the meeting, African leaders launched the Africa Climate Innovation Compact (ACIC) and the African Climate Facility (ACF) with the ambition of mobilising USD 50 billion annually for climate-related investments. This development demonstrated both Africa’s determination to shape its own financial architecture and the scale of the challenge it faces. While the new commitments signal momentum, they also draw into sharper relief the persistent structural barriers that have defined Africa’s engagement with climate finance to date.

Climate finance flows to Africa have grown in recent years, but remain far from sufficient. The Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) and FSD Africa reported that inflows reached approximately USD 44 billion in 2021/22, an increase of nearly 50 percent compared to 2019/20. Yet, this still represents only about 23 percent of the estimated annual requirement for the continent to achieve its 2030 climate and development goals. The Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) collectively disbursed a record USD 137 billion in climate finance globally in 2024, of which USD 85 billion went to low- and middle-income countries. However, mitigation accounted for roughly 69 percent of this total, while adaptation received only 31 percent. For Africa, this imbalance is particularly acute, as the continent is one of the most climate-vulnerable regions, yet adaptation projects continue to attract disproportionately little finance.

The structure and terms of climate finance present further complications. A growing share of funds is provided as loans rather than grants or highly concessional resources. The concessional portion of public climate finance declined from approximately 57 percent in 2018 to 47 percent in 2022. For many African economies already grappling with debt distress, this trend raises the risk that climate finance could exacerbate fiscal vulnerability. Studies indicate that several African countries are now allocating more to external debt servicing than they receive in climate finance, underscoring a “debt–climate squeeze” that undermines both fiscal stability and climate resilience. While innovative mechanisms, such as debt-for-nature swaps, have been piloted, including the Seychelles’ initiative, which linked debt restructuring to marine conservation, these remain limited in scale and dependent on strong governance and institutional capacity, which is not widely available.

The distribution of climate finance across the continent is uneven, as the ten largest recipient countries collectively account for around half of all climate finance to Africa, while the thirty smallest recipients together secure little more than a tenth. This reflects a preference for countries with established regulatory frameworks, higher credit ratings, and larger project pipelines, while fragile states and smaller economies struggle to attract finance despite their high vulnerability to climate shocks. Within countries, flows are often concentrated in large-scale mitigation projects such as renewable energy installations, whereas smallholder agriculture, rural communities, and informal urban settlements (sectors and populations that face the brunt of climate impact) receive limited direct support.

Many African states lack comprehensive regulatory frameworks for green finance, including standards for green bonds, carbon markets, and transparent procurement systems. Limited technical and administrative capacity hampers the preparation of bankable projects, leaving governments reliant on external partners to design and implement initiatives. High perceptions of risk, including political instability, currency volatility, and regulatory uncertainty, further discourage private sector investment, particularly in adaptation activities where financial returns are less predictable. As a result, private finance for adaptation in Africa remains negligible, with global estimates for private adaptation finance standing at just USD 1.5 billion in 2021/22.

Despite these obstacles, certain innovations have demonstrated potential. African sovereign and municipal green bonds, although still limited, have established precedents for accessing capital markets. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) has piloted blended finance facilities, such as the Managed Co-Lending Portfolio Programme One Planet (MCPP One Planet), which pools institutional capital with IFC risk-sharing to expand climate lending. Regionally, new mechanisms such as the ACIC and the ACF seek to create African-owned platforms for mobilising and managing climate finance. However, these initiatives are still in their early stages, and their success will depend on broader reforms in governance, transparency, and institutional capacity.

However, inadequate adaptation finance threatens to erode progress on food security, water access, health systems, and poverty reduction. While sectors such as agriculture, forestry, land use, and water have attracted large shares of finance, the overall volumes remain insufficient relative to the scale of climate impacts. The Global Green Climate Fund (GCF) has increased health-related adaptation approvals from USD 178 million in 2021 to USD 422 million in 2023, yet such figures remain modest in the face of escalating climate-related health risks. Without more predictable and equitable flows, Africa risks being locked in a cycle where climate shocks outpace efforts to build resilience, undermining the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The developments of September 2025, therefore, highlight a paradox; Africa is securing more climate finance than in the past and is taking steps to establish home-grown institutions to manage it. Yet the overall scale, composition, and distribution of these flows remain misaligned with the continent’s structural vulnerabilities and development priorities. The reliance on debt-based instruments raises sustainability concerns, while institutional and policy weaknesses hinder the mobilisation of private capital. The Addis Ababa summit has injected renewed political momentum, but the systemic challenges revealed by recent analyses indicate that climate finance will remain a defining and unresolved issue for Africa’s sustainable development trajectory as the international community prepares for the forthcoming climate negotiations.